A few weeks ago I had the great pleasure of attending a small salon on ethics, spirituality and religion. I was humbled by the intelligence and insight of the attendees: public intellectuals, authors, a professor of religion, and numerous successful executives and entrepreneurs.

It was one of the few intellectual discussions I have attended where the atheists were balanced by an equal number of theists. A few brief presentations by keynote speakers included Girard’s explanation of religion (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Girard), the taxonomy of the religious debate, and the relevance of religion in the 21st century.

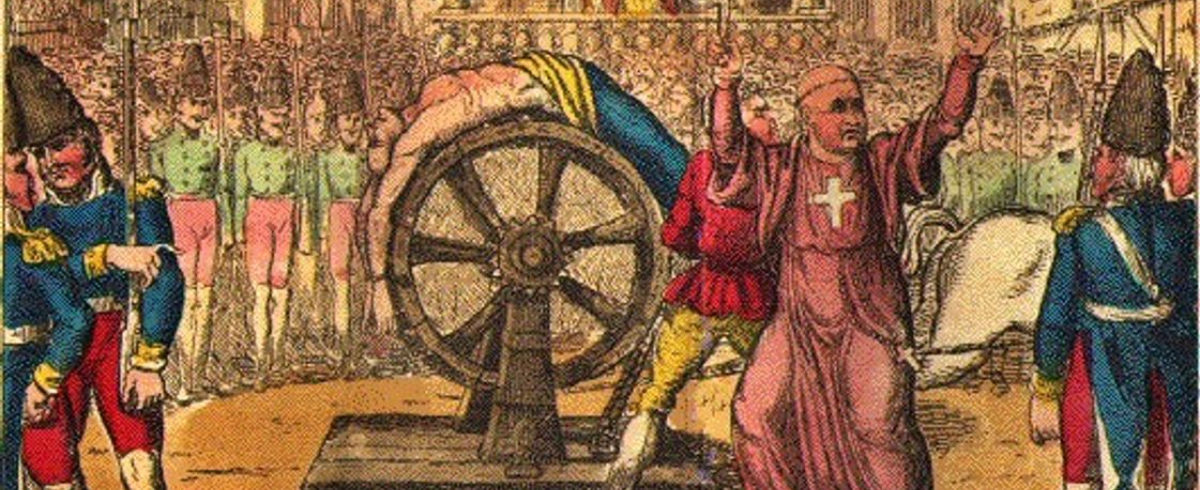

By far the most heated debate surrounded one theologian’s question: “Is it ever ok to do evil for good purposes?” and its corollary — a debate on torture. Instinctively, most people in the audience were against ever committing an act of torture. However, they recognized that Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler failed, and that the International Community could have limited genocide in Rwanda via the use of force. We would condone torture if the stakes are high enough, the outcome clear enough. In other words, most of us will “do evil” if we are sure it is “for good purpose,” such as saving a family member from imminent demise

As we tackled the theologian’s question on the merits of torture, we came to realize that our moral center is relative and highly dependent on the circumstances.

1. Framing & Ethics

If people are told: “There is an out of control train. It is about to run over 20 people. If you press this button, you divert the train and kill 1 person.” Most people press the button. If instead you say: “There is an out of control train. It is about to run over 20 people. If you push this 1 person in front of the train, you slow the train down enough to save the 20 people.” Most people do nothing. Yet the potential outcomes are identical in both cases.

2. Legality & Ethics

The definition of “torture” in international law differs from the definition of “torture” in domestic law,. Article 17 of the Third Geneva Convention states: “No physical or mental torture, nor any other form of coercion, may be inflicted on prisoners of war to secure from them information of any kind whatever. Prisoners of war who refuse to answer may not be threatened, insulted, or exposed to unpleasant or disadvantageous treatment of any kind.” The United States has adopted a more permissive definition of torture; it “must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.”

Perspective also influences the relevant ethics of torture. An individual may draw the conclusion that it is okay for them to do evil for good purposes. Simultaneously they may insist it is wrong for a society to legalize evil acts with a positive outcome. To illustrate, most individuals would engage in torture if they believed that the result would save family members from a certain demise. Yet a much small group would provide the government a carte blanche to institutionalize torture. Torture may be an example where personal ethics does not harmonize with a legal edict governing social conduct.

3. Efficacy

The most astute comment on the debate on torture came from one of the public intellectuals in the audience. He questioned whether the debate on torture should instead be a debate on efficacy rather than ethics.

He argued that we are uncomfortable with the use of torture because we are not convinced it works. We are not convinced the individuals we torture are guilty. We are not convinced that the people inflicting torture will necessarily extract information or instill fear. Moreover, even if we only torture guilty parties and effectively apply torture as an instrument, the very fact that we conduct torture publicly eviscerates our perceived respect for human rights and may actually be counterproductive to our long-term security.

Our ethical boundaries and beliefs were challenged. We left simultaneously enlightened and confused but at least having attempted to question the basis for our beliefs. And so the night ended.

Hi Fabrice,

What a great non sequitur to keep life interesting! Happy to see that you’re keeping busy with a new project. I’m starting work in Taiwan in just a few weeks now, very excited to get this new chapter of life rolling

+ the influence of our christian-jewish heritage about torture.

Muslims or Asian people may have a very different opinion on it

I happened to see Mercury Rising on TV two nights ago, and was struck by how well it captures the ethical puzzle you describe. The movie’s plot follows Bruce Willis as he protects a young autistic savant from NSA agents who are out to get him. The agents want to kill the boy because he cracked a secret government code. In a climactic final scene, an NSA agent confronts Bruce Willis and attempts to explain the ethical case for killing the autistic boy; he tries to point out that failing to do so would place the lives of thousands of innocent Americans at risk. But Bruce Willis kicks the NSA agent in the chest, dropping him and the topic mid-sentence. It was a solid kick, and it kind of epitomized the clash between personal and social ethics that surrounds the theologian’s question.

For further reading on the torture debate, check out:

http://balkin.blogspot.com/2006/12/anti-torture-memos.html#PartIII

Turns out we humans, even the nice ones, are not nearly as nice as we think we are. We’re quite egotistical. That’s the key. When you start realizing you are not a saint one comes to the realization that much of the time we just don’t do evil because its so much more convenient just to get along. In the end we do what we must.